![]()

![]()

Issue #23

October, 1997

©1997 A.D. Sullivan![]()

Just Like Ginsberg

Ma's Mad

An Editor's Note

Ginsberg Redux (1985)

Poetry in the Woods

Saying Good-bye (1997)

Last Words

![]()

![]()

![]()

Issue #23

October, 1997

©1997 A.D. Sullivan![]()

Just Like Ginsberg

Ma's Mad

An Editor's Note

Ginsberg Redux (1985)

Poetry in the Woods

Saying Good-bye (1997)

Last Words

![]()

For six years he meditated

under the fever tree.

In the sixth year

he contracted fever.

He bought gold sunglasses

and a red bandanna

and saw his disciples

with a glass of sake

in his hand.

He teaches the doctrine

of all things are permissible

but that doing very little

is a high path.

He said the proof of God's

existence is evident

around us:

the insanity of others

to which we are exposed,

by its sheer extent is,

of necessity,

divine.

The question is not is there

life after death but whether

there is life before it?

Sex is useless unless,

in the grip of fever,

we all make love

to our dreams.

There, at the perimeter,

with the stars behind us,

we become the people

we always though we were.

Such is the meaning of arrival.

Michael J. Maiello

Passaic County Jail, 1989

Ma's Mad

the way Ginsberg's was, dragging me around downtown

Paterson like a pull toy, using the collar of my coat

instead of a string,

The family on the hill at home, shaking their heads,

as stiff as William Carlos William's Great Falls face,

stone, stony, stoned,

bottles of booze in their veins,

Mad men for a man mother, drinking to forget

with me floating on the surface of their alcoholic dreams,"Poor boy," the family says, "Too bad he has a ma that's mad."

Planter's Peanuts, White Tower hamburgers,

catching the Public Service Number 3 from in front of town hall,

Me and Ginsberg, locked in a dance that isn't ours,

struggling to find ourselves among the mad eddies

of this mad river before it spills us over the great gap,

me and Ginsberg with nothing left but to write poems

about how rough the ride is.

An Editor's Note

9/26/97

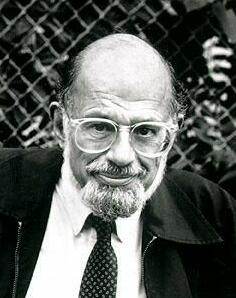

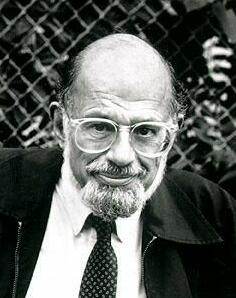

While I had heard of Allen Ginsberg many years earlier, I first met him after the Great Falls Festival in 1981 when he, drunk, tried to pick me and my friend Michael up in a jazz bar in Paterson. It was his birthday, and he seemed oddly alone -- despite the fact that every poet from Northern Jersey trailed behind him and hung on his every word.

I was always less impressed with the man than his work, though I later learned how wrong I was, how perhaps the man actually managed to overshadow himself, never quite able to make his poetry as powerful as his personality.

For all his potency as a poet, he served our generation as spiritual healer, from him and his contemporaries emerged the concept of "hippie" -- though Ginsberg's beloved' literary partner would later disown me and my kind, refusing to accept us as legitimate heirs.

I later meet Ginsberg when he was more sober, at a class as William Paterson College. Michael and I invaded the proceedings to grill him, and to find out why he had sold out to the main stream (he had done neither, but we were too impetuous to know that at the time). His disarmed us with his vast knowledge. I again have an opportunity to see Ginsberg at the Dodge Poetry Festival a decade later, but from a greater distance, when -- after a few years of decline -- he made him triumphant return as the king of poetry.

Finally, I would help mourn him, as part of a ceremony in Paterson, celebrating his memory with others in the very spot where I first heard him read in 1980. The three stories contained in his issue mark those moments of our contact.

Ginsberg Redux (1985)

by A.D. Sullivan and M. Alexander

We were looking for a corkscrew when the professor called us in to tell us there would be a new conference before the actual event.

What? Now? It was hard to think in terms of our media responsibilities when we had a bottle of five dollar wine waiting to be opened. We'd already tried using a key, but when that didn't work, we went inside, figuring one of the local reporters must carry a corkscrew for just such an occasion.

We were wrong. The familiar faces crowded the lobby of Rubinger Hall expectantly, with Professor Terry Ripmaster fluttering in front of them and handing out fact sheets on the man who had accepted an invitation to lecture his Cultural History of the Sixties class. One woman admitted she wasn't a reporter at all. "Ginsberg canceled when I had the class," she confided. "I guess I just felt cheated."

The big question among the better-researched reports was about Ginsberg's activities in the last few years.

"What happened?" One demanded. "What's he been up to?"

The others were lucky if they knew who he was. Earlier one college administrator had said the name was damned familiar. "I seem to remember a Ginsberg I had in school, years ago. But that couldn't be the same one."

As a matter of fact, that would be Allen's father, Louis Ginsberg, poet and teacher in Paterson (Even at William Paterson College, a teacher's college at the time called Paterson State.) Poet, yes, but not the same kind as his son, who had Howled at the head of the Beat Generation, who had danced through Be-ins in the Sixties, who had "OM"-ed at the Chicago Eight Conspiracy trial in 1969, who had won popular acceptance for his experimental poetics and who just now had a new volume of Collected Poems out with Harper & Row.

Perhaps he had a corkscrew: we had seen him before, drunk on his birthday in a Paterson jazz bar, listened to his talk about love and death (he seemed most impressed with death) while all around him would-be poets tried to impress him with their meters, as he had, generations before, impressed William Carlos Williams. What happened? What's he been up to? Well, he hasn't been hiding in his Buddhist-literary retreat, known as the Naropa Institute, in Boulder, Colorado. His poetry has taken him around the world in constant touring, with special projects netting in with his readings. He has recorded with musicians as diverse as Body Dylan and the Clash. He continuously protested US involvement in countries such as Nicaragua, and lectures on the CIA and nuclear politics. And on little gigs, like this, and one can see he is a busy man. We decided not to bother him for a corkscrew.

Before the reporters, he brought out newspaper clippings and reports about how the world had turned itself back into the kind of place he had begun protesting in the fifties, with tell-tale nuclear build-up and paranoid spy cases -- the Walkers substituting nicely for the Rosenbergs. He discussed the military, an estimated $20 billion, to rewrite history and repopularize the Vietnam war. A reporter clicked off her tape recorder as he began to name the corporations that were funding this Pentagon project, in order to save room on her tape in hopes of poetry later.

Ginsberg showed himself able to play the grizzled warrior as well as the feisty elf. A teacher asked him if his work was becoming more academic, and was this indicating a closing of rank between the experimental and scholastic camps?

"That's a load of shit," the poet answered coolly.

He cited Corso, Sndyer, Lamantia, Creeley and others of his friends, who, he said, were not receiving grants, notice or acceptance of any kind from the Academy of American poets. He accused his critics of having less discipline, understanding of meter, or poetry in print than he. For him, the battle continues. We moved down to the lecture hall to distribute our subversive literature, past copies of Scrap Paper Review. The room was full and would soon overflow; still nobody had a corkscrew. Ginsberg arrived, and began to speak about the Spiritual revolution that had begun with the Beat poets (more truly a lost generation than the expatriates, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Stein, etc.) And come to fruition in the Sixties. He read Robert Creeley's poem "The Conspiracy," in which two poets conspire to send each other poetry, and went on to read thirty or so other points on poetry by Jack Kerouac.

"Listen."

"Be a genius all the time."

"Be aware of the day and time."

(Ginsberg then erred at to the day)

"And don't be afraid of being stupid."

(Such as not knowing the day.)

Ginsberg defended the psychedelic (with a long E on the third syllable) experience as a realization of "the world alive." The psychedelic observer becomes one with the world observed; schizophrenic meaning is found in any sound or shape.

(Note: acid propaganda of this nature must be taken with salt pills. Not every dosage of everything called LSD produces such effects.)

In a footnote, Ginsberg noted that the atomic and psychedelic ages began in the same year: 1945. Exactly forty years ago, the bomb was dropped and lysergic acid was developed, beginning what Ginsberg terms "the spiritual revolution."

In the most impassioned moment of his presentation, Ginsberg asked some of the inescapable questions that lead to rebellion. "How come the movies say people who smoke marijuana go to the boogie house and I smoked it and I didn't go to the boogie house?"

"How come the greatest jazz musicians weren't allowed to play New York City clubs, which were owned by the Mafia anyways, just `cause they'd been busted for marijuana?"

"How come the CIA introduced opiates to China and now they tell us the commies wanna bring it here to corrupt us virgin Americans?"

"How come we bomb Nicaragua harbors and call them terrorists?" Everyone must ask themselves:

"How come the establishment breaks its own rules, and, in asking, begin to expand ourselves beyond the previously allowed barriers. This is where the revolution begins."

Ginsberg is 59 now -- almost thirty years past the distrusted age of thirty -- and still plays the fifties/sixties elitism that separates the world into "cool" and "uncool," or, in literary terms, "combed" and the "uncombed." Beat poets once claimed the literary tradition of wild, inspired poetics, valuing experiment over versification. Ginsberg tied into this tradition through William Carlos Williams, leading innovator of the time, in the same way, Dylan identified himself with Woody Guthrie, proselytizing and perhaps prostituting their mentor's messages the masses would understand. Both men have turned profit out of prophecy. But would the words have been heard without some shouting? Even so, have any heard?

Ginsberg declined requests to read his recent work. He was fishing for questions about the Sixties. The reporters (at least the ones with tape recorders) were slightly disappointed. The Herald & News managed to catch the "spiritual revolution" drift, as well as points of "hyper-technical" threats to our existence, though its coverage made the talk seem more serious than it had been. The Bergen Record lead with rumors that Ginsberg might move back to Paterson, clearly, for better or worse, the most news-worthy element of the evening. At the end of the event, Professor Ripmaster asked the press credit the History Department of the School of Humanities of William Paterson College. None did. We returned home to our own kitchen corkscrew, and finished off the wine without further ado.

Twenty five years from now, it is unlikely your children or grandchildren will ask if you attended the 1996 Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival the way kids today ask their parents about Woodstock, and yet pulling into the parking lot and walking up the wide paths from the road to the festival site, the feeling was largely the same -- though this was a four-day festival from Sept. 19 through 22 and the rain didn't start until it was nearly over.

Maybe the lines weren't quite as long for the telephone booths, though Barbara Stewart, of the New York Times, did complain about the line outside the women's room. The food was better, too, veggie burgers and heath snacks, with cases of bottled water. Woodstock didn't have Pizza, either, and the announcements from the main tent dealt mostly with mis-parked cars or headlights left on.

Borders Books, which opened its first store in Manhattan's World Trade Center building earlier this month, had its own tent, selling the books of the poets who were to appear at the festival. They sold remarkable number of books as did the other vendors selling T-shirts and posters, and despite the last day of rain, more than 10,000 people attended the four-day event, making this the largest event of its kind in the United States. The 1994 edition of this every two-year event was featured in the Bill Moyers PBS series "The language of Life."

While hardly the household names that performers like Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin have become since Woodstock, some of the most important names in poetry came to this year's festival, including Allen Ginsberg, Phillip Levine, Galway Kinnell, Lucille Clifton, Maxine Kumin, Karylyn Kizer and Donald Hall. Although the 91-year-old Stanley Kunitz was also scheduled to appear, he caught cold a week earlier and chose not to come.

Also included were the 29 winners from the New Jersey High School Student Poetry Contest and countless other poets and wanna-be poets, who spread across the setting with impromptu performances of their own. In fact people came from up and down the east coast, with a few poets coming from as far as California and, Waterloo Village with its 18th and 19th century buildings, working gristmill, sawmill, church, general story, tavern, blacksmith, apothecary and recreated Lenape Indian Village, made a perfect backdrop.

Hudson County had its share of representatives. Guttenberg's Dodge Poet Larua Boss was there. So were Hoboken poet and publisher, Danny Shot, and Hudson County's unofficial Poet Laureate Joel Lewis. In fact more than 4,000 students, teachers and poetry fans showed up on Thursday and Friday with many more coming over the weekend despite the rain on Sunday.

In a way, this was a tribute to the power of New Jersey in the growing poetry scene, with cheers going up repeatedly in the big tent every time New Jersey was mentioned or a poet claimed residence here. In fact, poets and writers from Riff Magazine, a new literary magazine from Edgewater took over one of the open reading sessions, the way they had invaded a reading at the Hoboken Barnes and Noble a month earlier. Poets proffered their prolific poems to the gurgling waters of the Morris Canal, talking about trains, planes and heart aches.

Although Ginsberg stole the show, Pulitzer Prize-winning Philip Levine filled the 1700 era Church with his talk about the nature of poetry and was the top act at the big tent closing Friday night. As a professor of literature at New York University, Levine said he is constantly confronted with parents who have an apparently more practical future for their children in mind. He said he remembered one student's parents calling him up saying their son wanted to be a poet.

"They wanted me to talk him out of it," Levine said. "I told them the boy would have to make up his own mind."

In the course of the conversation that ensued, the parents protested, saying they wanted their son to become a doctor. "They said they were a professional family. I told them poetry is an ancient and honorable profession," Levine said. "Later, their son became a fairly successful poet. They seemed to have forgotten where the phase came from when they proudly told me that poetry was an ancient and honorable profession."

For the first few days, people kept asking "When's Allen Ginsberg coming?" and mistaking other older men they saw on Thursday and Friday, although he was not scheduled to appear until Saturday afternoon. He did a benefit reading at Columbia on Friday, celebrating also the release of his new book, "Selected Poems." When he climbed out of the car people of all ages swarmed around him, treating the man like a superstar. It was a marvel just how popular he has become after being spit upon by the remarkably conservative poetry society in the 1950s when his work first emerged.

Ginsberg was a discovery of Williams Carlos Williams, perhaps the greatest 20th Century American poet. Ginsberg came to William to show his poetry the way many of the kids at this festival came to him to show him theirs. Williams shook his head, saying it wasn't good enough, and then, Ginsberg showed Williams some journal entries he'd made from trips across country with Jack Kerouac, powerful and intense jazz-like language that began a revolution in writing. Williams told Ginsberg: "This here is your poetry." Ginsberg had grown up in and around Paterson, gleaning lessons from that historic city, and from the thriving sense of life that still exists there. I got drunk with him (though he would not remember) at his 55th birthday party in Paterson, after a Great Falls Festival in 1980. But in 1985, my friend and I, cornered Ginsberg during an interview he held at William Paterson College. Ginsberg's Collected Poetry had just come out from Harper & Row, the first time his work had received acceptance from a national publisher. We thought he had sold out and told him so. Now, a decade later, he proved us wrong. Success had not ruined the 70-year-old poet, but had deepened his conviction to poetry, so that above all others at the festival, he was the grandfather of poetry, the wise old man who had come to teach the children the rituals of the muse.

James Haba, coordinator for the festival called Ginsberg one of the "absolutely great literary figures of our century."

But it was a small man with a loud voice that sat down before the waiting crowd of thousands, his music box on his lap, his eye glasses slightly askew, yet he managed to sound larger than life. This is the man who crossed country with Kerouac in 1949, the man who set the poetry world into shock when he read "Howl" in San Francisco in 1956, the man who was carried out of the Chicago 8 Trial in 1969. He was the man who had breached the Iron Curtain in 1968, and returned when the Iron Curtain fell to rust in 1990. Above all others at this year's festival, Ginsberg made poetry sound like fun. He sang it. He cursed with it. He chanted it. He protested through it, and under the big tent he kept people riveted to their seats, none daring to blink for fear of missing something. Over the years, Ginsberg has grown weaker with various diseases, some of which he listed jokingly during his protest song against smoking. And he may not be with us much longer, and yet, for one sparkling moment, at one great occasion in the woods, we met him again and he shone, receiving the kind of accolade as a poet of which Plato would have been proud.

They sang, huddled together along the rail overlooking the Great Falls in Paterson, the sound of water playing bass to the dirge they sang in honor of Allen Ginsberg's passing, the stone face of the falls echoing their weak voices.

Poet Williams Carlos Williams once saw an old man's face in these falls, long before he discovered and helped Ginsberg to become a poet, long before Ginsberg began to resemble the old man of the falls. For years, Ginsberg celebrated here, reading his poetry, listening to the poetry of those who loved him.

And on June 8, 1997, four days after what would have been his 71st birthday and two months after his death, Ginsberg's followers came to sing and remember. Poets and politicians sang songs Ginsberg had written himself, each clutching a white piece of paper with the lyrics written out, struggling to make themselves heard above the lush fall of river water descending into the dark brown chasm of stone.

Ginsberg grew up within blocks of this place, but he left his mark across the state, on the faces of those who had come to Paterson to say good-bye, faces of the poets and writers who he had helped over the years, many of whom had met him here, during the mid 1970s to the early 1980s.

"Hey father death, I'm flying home," sang Guttenberg's Laura Boss, the wind blowing her long black hair across the poet's squinting eyes.

"Hey poor man, you're all alone," sang Hoboken poet, writer and publisher Danny Shot as he stared over the shoulders of the people in the crowd.

"Hey old Daddy, I know where I'm going," sang Hershel Silverman, a Bayonne poet and close friend of Ginsberg, his hand gripping the rail.

Nearly a hundred people gathered to honor Ginsberg, from his stepmother and brother to the man who wrote about Ginsberg's 1966 arrest for the now-defunct Morning Call. Most of the people who came to the event wanted to share a memory of the man that the New York Times called "The Poet of Our Generation."

While Jersey City poet Sharon Griffiths read an original poem based upon her seeing Ginsberg over the years and her extensive reading on the Beat Generation, most of the others told brief tales of meeting the poet and how they felt about him.

Among those who came to honor him was US Rep. William Pascrell, the former mayor who had welcomed Ginsberg back to Paterson, voiding a 25-year-old warrant for Ginsberg's arrest. Pascrell's predecessor, the legendary Mayor Frank X. Graves, ordered the police department to issue the warrant in 1966, after reading an account in the local newspaper in which Ginsberg admitted "smoking a joint" near the Great Falls.

Ginsberg has been described as having "a contempt for convention," emphasized best by his well-known poem "Howl," which he read and published in 1956, whose purported obscenities caused an uproar that led all the way to the United States Supreme Court (which found in favor Ginsberg's right to self-expression). While one conservative local councilman raised objections to the June 8 tribute, this seemed only to rally Ginsberg's friends, making their remarks more defiant, as each was trying to send a message eight blocks to town hall to say: Ginsberg was Paterson, as he was Hoboken, and Jersey City, and Bayonne, each place shaped into his poetry, each era preserved in a bottle of words for future generations to sip.

Poet Eliot Katz, who helped found the Hoboken-based literary magazine Long Shot, said the publication would not exist if not for Allen Ginsberg's support. Co-editor Danny Shot and Katz met Ginsberg in 1976, when the poet gave a reading at Rutgers.

"He split the money from the door," Shot said, and then continued his support by giving the magazine unpublished poems to print. Laura Boss said she met Ginsberg in Paterson in June 1979, at the Great Falls Festival. She nearly ran him over after the event, when she was backing out of a parking place.

"He had some very choice words for me at the time," Boss said. "Later we became good friends."

Hershel Silverman knew Ginsberg for nearly 50 years. Ginsberg and the other Beats used to come to his candy store in Bayonne. Silverman remembered a more recent visit, when Ginsberg even helped carry in the morning newspapers.

Hudson County was a kind of second home to the Beat Generation, many of the central characters such as Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso and others used to take the Hoboken ferry over from Christopher Street to carouse in the bars and fish food establishments along River Street.

Most of the poets who knew Ginsberg during the last 20 years of his life did typing work for him. He had terrible handwriting and always needed his poems typed. In exchange, he looked at their work, helping them shape it into better poetry.

It was a worthy exchange.

Allen Ginsberg was a larger-than-life figure who was never too large to say hello to a person on the street; he would stop and talk to the homeless, he would help his friends. He knew what it was like to be homeless and poor.

Sometimes as a boy in Paterson he had to sleep on the floor of his mad mother's house, and yet rose to become one of the most celebrated people in the world, his style shaping this whole half of the 20th century. In its obituary of Ginsberg, The New York Times said Ginsberg influenced a generation from Abbie Hoffman to the Smashing Pumpkins. Bob Dylan called him the greatest influence on the American poetic voice since Whitman.

Ginsberg helped create the 1960s, and had a piece of every part of it. He was with Timothy Leary at the beginning of that era and at Woodstock at its end. He won the National Book Award in 1973, toured with Bob Dylan in 1977, and visited Eastern Europe in 1986. He protested before the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago and was thrown out of Cuba in the 1970s for protesting that government's treatment of gays. Most recently he recorded his poem "The Ballad of the Skeletons" with Paul McCartney and Phillip Glass.

"But he cared about people," said Boss. "And he had a lot to give."

The last words, you tell me

you have decided with your

friends, that will be

spoken by the majority

of people on the moment

of thermo-nuclear attack

will be something common,

some everyday obscenity,

two words, you remember,

but not which two.Can you recall,

how many letter each?

Can you give me something

to go on? To piece together

the utterance obliterated

by your memory? If only

I knew what they would be,

I could practice those last

words now until their moment

of use, to perfection.

M. Alexander

All work is by A.D. Sullivan except where otherwise indicated.

Those who wish to comment can do so by e-mail to 110366.2534@compuserve.com or by traditional letter to:

SPR

PO Box 765

Hoboken, NJ

07073