Issue #39

March, 1999

©1999 A.D. Sullivan

![]()

![]()

Issue #39

March, 1999

©1999 A.D. Sullivan ![]()

![]()

You can't shoot winter like you can a racoon, though for five months it's stared at you at night, defying you to kill it.

When it dies, it keeps you up at night with its stink, the bursting buds of spring time making their way up through the clay,

earthy smells assaulting your nostrils after months of smelling snow.

You see it dying when you walk from door to truck, cracked brown palms breaking up with flecks of green, sucking up rain

water, burying winter in pools of melting ice, cobblestones breaking free, poking up through the surface, a sad sight making you

think the world is melting, making you believe it will never come together in the same way again.

I don't hate spring or summer, but I look forward to fall, and crave the silences of the winter, the closed windows that cuts off

the sound of traffic and construction, the yelling of kids, the back and forth shouting of my neighbors. In the winter, you can

crouch down under camel hair and think, with only the on and off of the heater to disturb you.

Seeing it die, is like losing an old friend, watching its body decompose, replaced by noise of spring time and the shouting joy of

people discovering the world again, as if they were afraid to venture out where the sting of cold could get them. Winter always

stings, never coddling you, never pretending the world a pleasant place.

But it dies so slowly, bits and pieces falling from roof top gutters, cracking ice as terrifying as snapping bone. You want to put

it out of its misery, want to shoot it between its eyes, the way you would an old moaning hound or a half dead road kill

raccoon. But you can't, and suffer along with it, until the groans stop, and spring leaps over its corpse.

You can't kill spring either. But that's a whole other story.

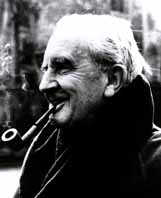

Tolkien, Lewis and the Critics

Text of a talk given at the Newark Museum on March 4, 1999

I first read Tolkien in mid 1970, during one of the most tumultuous times in my life. I was “On the Road” as Jack Kerouac put it, and Tolkien seemed to connect with that spirit.

I read CS Lewis later, and discovered that both he and Tolkien seemed to believe that you had go take a journey out of your own life to discover what your life really means.

I was in Los Angeles at the time, and was told by the staff of the legendary Free Press that the book would change my life. It did, creating a hunger in me to do something with my life that could roughly echo what the book did. While I had aspirations to write ever since grammar school, I suddenly wanted to create something as grand.

Since then I have read “The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings” about 40 times, studying the work -- not so much as a scholar but as admirer, seeking to learn the secret of how he did what he did, so I could apply it to my writing.

Basic literary criticism tends to have two extremes: interior and exterior.

Interior criticism looks at a work without bringing to it outside criteria. No biological material about the author which might shed a light on the material. This kind of critic uses only the text.

Exterior criticism can use anything that will explain what an author does. Exterior brings material from an authors past to explain influences on the text.

Many use variations of both.

When dealing with Tolkien and to a lesser degree Lewis I stick to the material alone. I also do not use anything beyond the Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in my study. While I have read most of his other works, including the volumes released by his son, Christopher. I do not consider them primary.

When dealing with Tolkien and to a lesser degree Lewis I stick to the material alone. I also do not use anything beyond the Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in my study. While I have read most of his other works, including the volumes released by his son, Christopher. I do not consider them primary.

For those who are not aware of it, Lewis and Tolkien were members of a Oxford University writing group called the Inklings. This included CS Lewis, JRR Tolkien, TH White, W.H. Auden and others. My wife calls them the men without first names, because all used initials in publication.

"The inklings, which existed from the mid-1930s to 1962, were a highly informal group of Oxford writer sand poets who met regularly in college rooms and local pub to read their works in progress," said Daniel Grotta-Kurska in his book JRR Tolkien, Architect of Middle Earth. "According to CS Lewis, they discussed everything from beer to Beowulf."

Auden challenged the members of the Inklings to produce a modern tale of Christian beliefs. Out of this challenge emerged the Tolkien Trilogy, Lewis’ trilogy and White's "Once and Future King.

This group helped shape the concept of modern fantasy and produced books that influenced many of the modern writers. Tom Clancy claims Tolkien molded his fiction, even though Clancy writes what is considered a extreme modern technical thriller. I've written numerous failed novels in an attempt to duplicate Tolkien's achievement, and after years of studying him discovered, as Clancy has, that it isn't the model or themes that I should imitate, but the dedication to creating as complete a fiction as possible, giving each of the characters life.

Both writers created something relative to Christian stories, although only Lewis was accused of writing propaganda. Tolkien, whose tale did not mention God or Christianity, seemed more palatable to some, while Lewis was accused of being a propagandist for the Christian faith.

"Tolkien's treatment and incorporation of religious themes into The Lord of the Rings, however, is nothing less than extraordinary," Grotta-Kurska wrote. "Middle Earth is a pre-Christian world without Original Sin, and therefore without the need of Christ. There are no gods, saints or ritual."

"Both Lewis and Tolkien are Christians," writes Dr. Richard Purtill in his study of these two writers. "This is so clear in Lewis that we have found critics accusing him of propaganda. It is much less clear in Tolkien, and this has tempted some critics to say that Tolkien's view of the world is really the modern view and not the traditional christian view."

This, according to Purtill, is a major misunderstanding of Tolkien's work.

One critic, Roger Sale, makes this claim for modernism in Tolkien, but Purtill view this as inspired by Tolkien's source, largely the Northern Mythology the author used as part of his subcreation.

"In fact Tolkien and Lewis both have a profoundly Christian view: This world is a vale of sorrow and struggle and we must look for real consolation only after death or after the world ends," writes Purtill.

Both Lewis and Tolkien also were accused of writing an allegories, something both denied.

Lewis, who read Tolkien's work in progress was very vehement on this point:

"Tolkien's book is not an allegory -- a form he dislikes. You'll get nearest to his mind on such subjects by studying his essay on Fairy tales in the Essays Presented to Charles Williams," Lewis wrote in a letter to Fr Peter Milward in 1956. "His root idea of narrative art is subcreation, the making of a secondary world. What you would call a pleasant story for children, would be to him a more serious than an allegory."

Tolkien himself condemned the idea of allegory in the forward to the Ballantine edition:

"I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestation and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the though and experience of readers. I think many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader and the other in purposed domination of the author."

According to till, Tolkien's theories on fairy tales were very clear.

"The story maker can be a successful subcreator," Tolkien wrote. "He makes a secondary world which your mid can enter. Inside it, what he relates is true, it accords with the laws of the world. You therefore believe it while you are, as it were, inside."

"Tolkien suggests," said Purtill, "that if handled correctly, this could be the most potent form of narrative art or story telling."

Aimed, in Tolkien's idea, at laying bare the secrets of the human heart.

Purtill said Tolkien and Lewis could have used allegory, but did not, inventing instead something called "Illustrative fantasy."

"The author which to make a point about some aspect of the primary world which can best be made by isolating or exaggerating certain aspects of that world by the use of a secondary world," Purtill said.

This is sometimes called appreciative fantasy, designed to provide recovery, escape and consolation to the reader, giving back to the reader something he or she has lost over the years, a sense of wonder and mystery, allowing that person to escape for a time from the pressures of the world, especially the pressure exerted by thoughts of dying. The fictions designed by these two authors were deliberately aimed to provide consolation by their happy ending, giving the reader what Tolkien called "a glimpse of joy."

"Tolkien's view of fairy stores is not just a view about literature, but a view about life," Purtill said. "For in Tolkien's view the important secret of the human heart is his long for the real happy ending. And the most important thing about this long is that it can be satisfied."

Both authors see the world as a place of wonder, and that the modern world seems increasing to become a place of ugliness and misery, and that the christian story gives consolation by showing a world that ends in joy.

Both Tolkien and Lewis created characters that were largely all good or all bad, but the focus of their stories were on those characters that had to choose, corruptible beings in danger of being swayed towards evil.

Nature is generally seen as beneficent.

In Tolkien, a forest is made evil for instance, if it has been occupied by evil beings. Thus it must be cleansed. Good people, particularly elves in Tolkien, can make a place more beautiful

In both Lewis and Tolkien nature acts almost as a character in the drama, such as The Old Forest in Tolkien's book.

"The opposition of the Shire and Mordor is essential that of Logres and Britain," wrote Charles Moorman in his study of the city in Tolkien's work. "Both the Shire and Logres are agrarian societies, simple and quietly governed. Both value the rights of the individuals and preserve the worth-while values and traditions of the past. Mordor and Briant are false progressive, both complex, industrial state in which the individual counts for very little and the past for nothing."

Tolkien’s main subworld is Middle Earth, a place in which “The Hobbit,” the Lord of the Rings, and other works takes place. Lewis created two main subworlds, one for his trilogy, another for his children’s books, the Chronicles of Narnia. But in the books of both authors, the main themes centered around the conflict of Good v. Evil and the need for each character to choose between them.

One of the chief differences between Tolkien and Lewis is in their use of language. Although the creator of one of the most magnificent worlds in fiction, Tolkien deliberately chose not to be too descriptive, giving descriptions that are largely "general" in order to allow the reader to create his or her own mental pictures. Lewis, however, gives every detail possible, deliberately painting a s complete a picture as possible.

"When we look back at the uses of language by our two authors we can see similarities," wrote Purtill. "Both use language to reveal character, both connect language and rationality. But beyond this there are differences -- perhaps only differences of emphasis, but important nevertheless."

Tolkien gives depth to his fantasy by use of material outside the text, or material referred to within the text, family histories, chronological events and such. He was a master of language, and often used language as a means of identifying characters, good characters talked smoothly, bad coarsely, although in some cases, the more devious evil characters talked too smoothly.

Lewis was interested in how words changed meaning, and the misunderstandings such changes can cause among characters.

Both authors use language to reveal characters, both connect language and rationality.

But Tolkien turned his language into poetry in an effort to sway readers to his point of view, while Lewis used language as a tool to teach.

"Tolkien uses language to weave enchantments; his use of elvish or orcish words can establish a mood, can create belief in us," Purtill said. "Lewis uses language to convince, to enlighten, as well as to make us picture strange scenes and strange beings. Both are poets, both are teachers. But in Tolkien, the poet predominates, in Lewis the Teacher. Both use language to change the way we look at the world, but Tolkien, we might say, works through our emotions, while Lewis works through our intellect."

To begin with, Tolkien wrote what we might define as pure fantasy, Lewis wrote-- in his adult stories -- science fiction.

Tolkien deliberately adopted an archaic style to helped give his work depth, relying on classical or stock symbols to evoke a response in the reader. Such as using “the sword of a king” as a symbol of power.

Lewis used a much more modern style of writing, using metaphors to create strong images and tighten his language.

Unfortunately, this modernistic approach did not bring to Lewis the same influence of genre science fiction as Tolkien had upon fantasy. This was partly due to Lewis's twist of logic.

HG Wells, one of the father’s of Science Fiction, and perhaps the person whose influence on Science fiction can be best compared with Tolkien's on Fantasy, shaped the genre’s approach

Wells as for much of science fiction created good characters out of scientist, the political left and others who approved of progress, and shaped its evil characters out of religious leaders, and others who had unshakeable moral values or sang too loudly the song in support of tradition. This has changed with later science fiction, but not when Lewis published

Lewis's science fiction did exactly the opposite, turning the genre on its head. Progress could be a bad thing, and those who pushed too fast and ignored such things christian principles and justice, are evil.

"Although Lewis's supposed anti-scientific attitude has been exaggerated by critics, there is some tendency in his books to idealize the bucolic and primitive and to show the dangers of science and technology," Purtill said.

While Tolkien’s tales were equally opposed to progress for progress' sake, his setting in fantasy and by emphasizing the more traditional tone of voice did not grate on people’s nerves the way Lewis's works apparently did.

Because Lewis created subworlds which were much more overtly Christian than Tolkien's, he suffered accusations of writing allegory or acting as a defender of the faith. He resisted such attacks, believing his stories could be enjoyed for their own sake.

Much of the attack on Lewis’ work may have been unfounded. He did not write allegory, nor was he an apologist for Christian values. And in many ways, his work lived up to one of the fundamental principals of Science fiction roughly called “What if...”

He created characters and put them into fantastic situations with the question of how they might react, allowing them advance the story based on their characters.

"Lewis is interested in these supposals partly for their own sake and partly because they provide a restatement in new terms of ideas Lewis held to be true on other grounds." said Purtill. "But those who think Lewis intended his fictional works as arguments for Christianity obviously have little idea of what argument is. Lewis did, and he gave very good arguments when it was his business to argue."

Over time, Lewis has survived his critics and come to acclaim, partly because of a growing Christian movement that took him on as their philosopher, but partly because he was a brilliant writer with substantial ideas. He was also a significant literary critic, whose ideas bore weight in the world beyond the christian community.

In some ways, Tolkien fared less well. He suffered from a differ dilemma: popularity.

Because so many people imitated, and because a whole genre of fantasy emerged as a result, he was later ignored by serious critics who lumped him with inferior sword and sorcery writers.

While serious criticism did exist in the 1960s from Edmund Fuller, Roger Sale, Hugh T. Keenan, Robert J. Reilly and many others, the 1970s saw a decline that has only recently been reversed as critics begin to understand his significance as a literary figure. Some critics saw his work as the bible of the hippie movement.

While Tolkien, considered a brilliant teacher, wrote literary works during his life, these were often so specialized that they were not accessible to the general public.

This misconception, fortunately is changing as a new generation of critics have begun to look on Tolkien as the master craftsman he is, and began to study his work again as literature, and not merely a fad.

I followed William Stafford

to Pine Cone Country one year

after the moon had become

a bull's eye for wandering rockets,

the sound of chain saws and falling trees

erupting from the mountain--

Mount Hood awesome with its white dwarf cap

shimmering under a summer sun

while the river, Columbia,

raced beside the highway

as if it could win

against the Eastern Establishment

and water pollution,

telephone lines and laser reflectors,

the moon's face looking down

laughing over the frosted waves,

saying rockets must come to all,

and in the Spring of that year,

you and I, standing on the side of the mountain,

watched them fall.

Douglas Neffer hadn't visited here in over a decade, since before Nixon and Watergate helped ruin the counter culture for him, and all that other crap Neffer used to believe in.

He felt stupid for coming back, the sharp edge of his business suit rubbing his thighs the way his old jeans never did, and the brief case tapping his leg as he walked the way his leather pouch once did.

The residents of St. Marks eyed him strangely, too, though the neighborhood had changed enough to make Neffer's kind less uncommon than in the past, young professionals parading from the Astor Place subway station as if they owned the streets, shoving hippies and old ladies out of their way with their arrogance.

Only Neffer seemed disturbed by the new generation of hippies that inhabited the blocks between the Bowery and Avenue A, purple mohawk haircuts replacing the dirty long hair Neffer had worn, leather pants replacing the jeans: nose rings, eye rings, and posts through their tongues, full of promise of violent protest -- but protest of what?

Neffer, for all his parents wailing over his appearance, had never looked as awful as this. His long hair had never seemed so alien, despite the way he had dressed. It was as if he had climbed up from the subway into a different planet. The most extravagant he'd ever gotten was to don a Sergeant Pepper's jacket and a few strings of beads. He could not even imagine himself dressed as these kids did.

Yet he understood this new look was an evolution of the old, a transformation of character that Darwin could have well explained, each batch of new kids pushing the envelop of acceptance that much further beyond where the previous batch had gone. Neffer had simply missed witnessing the middle stages, especially those stages that had twisted "love and peace" into something obscene, men and women now glorifying violence.

What did they call them? Skin heads?

He never once believed that the values he'd adopted here would lose their appeal. But then, he had abandoned them to start a family and begin a career. So he could not bitch about others taking the movement some place he'd not intended.

He tried not to look around too much, but he was looking for a particular door, and had to peer around the worst of this crowd to make sure he didn't miss it.

That one door that he had come to so faithfully it might have served him as a church, each weekend he and his friends from New Jersey arriving here first before wandering off to study the rest of the Village's secrets.

Then, as he thought of it, the door appeared, and its rusted rail, and the cluttered stairs leading down to it from the street. Seeing it for real, not just in memory, gave him a start, and his free hand gripped the rail to keep himself from shaking.

"Am I crazy?" he thought. "The Old man isn't going to be here -- not after all this time."

Even if the old man had survived gentrification; even if the local punk scene hadn't beat him up and left him for dead, Neffer had no right to come back, to seek answers from the very man he had vowed to disown.

The shame -- which Neffer felt when he originally broke from his guru -- returned, magnified by the years.

"What if the old man asks me why I stopped coming?" Neffer wondered. "What would I tell him?"

That he had stopped believing in foolish schemes for universal salvation? That Humans were not meant to find enlightenment or seek perfection? That the central flaw of mankind -- greed -- could not be overcome with incense and chanting?

All those things that had seemed so true to Neffer in the past, now seemed hollow excuses he dared not present to a man so wise as this old man -- as hollow as Neffer's knock when he finally managed to ease down the slippery steps to stand before the door.

The old man believed in perfection, and Neffer did, too -- only not for himself.

His knock echoed in emptiness. He listened, but heard no whisper of feet, only a silence made more intense by the street noise, the record shops and book stores and jewelry hockers filling up the street with their racket.

"He's dead," Neffer said.

But the silence proved nothing; it was always a place of vast silences.

"He's dead," Neffer told himself again. "As dead as his beliefs."

But a moment later, the door opened, and the old man stood before Neffer as if time had stopped inside, old but not old, the dark eyes as full with the universe as Neffer remembered. The bare feet and the nehru shirt were the same as well.

"Douglas?" the old man said. He did not sound surprised so much as intrigued, as if he had waited a long time for this moment and now wanted to learn more about the circumstances that had brought his prize pupil back.

"Hello, Mr. Gerani," Neffer said.

"No more, Guru, Douglas?"

Neffer blushed. "I was younger then. I called many people different things."

"Of course you did," the old man said. "Come inside. It means nothing to me what you call me by. I am always the same."

Neffer took one step, then another, and indeed, it was as if he had stepped through a door in time, returning back to that very first vision when he had come here as a novice, the burning incense and the thin floor mats making the place seem exotic.

This time, he almost forgot to remove his shoes, just as he had not done the first time. He balanced himself on one foot, then the other, and felt even more foolish standing in his stocking feet. Now, he only had his business suit to protect him.

But protect him from what?

The old man motioned him to sit; Neffer sat.

"So what has brought you back, Douglas?" the old man asked, sitting himself down across from Neffer, just as he had always done.

"I don't know exactly," Neffer said.

"And you think I do?"

"I was kind of hoping..."

"Many come with questions about themselves," the old man said.

"But I swore to give you up?" Neffer said.

"Do you have a particular question?"

"Yes, maybe, I don't' know," Neffer said. "I thought I did. But my mind is full of confusion. I've changed so much from the person I was, I'm not sure I know how to make it all orderly again."

"And you need order?"

"It would seem I do," Neffer said. "One day I woke up and I didn't like who I was, even though I've worked very hard to become this me."

"You mean you're unhappy?"

"No, that's the wrong word. I'm happy after a fashion. I'm just missing something."

The old man nodded, his yellowed teeth showing what might have served him as a smile. He unfolded his legs and rose, and moved to a curtain at the end of the room. He pulled this open, revealing a window. Beyond it, construction showed, one more old building vanquished, begging gutted to make way for professionals like Neffer.

"What do you see here, Douglas?"

"See? You mean the street?"

"Who do you see?"

Neffer frowned, and then shook his head. He hadn't played the perspective game since giving up the old man's instruction, but he knew the rules.

"I see people, of course."

The old man let the curtain close and then shuffled across the room to another. He opened this set with a little more care. They revealed a large mirror.

"And now? What do you see?"

"Myself," Neffer said.

"Both are windows of a kind, are they not?" the old man asked. "Both made of glass."

"Yes."

"Add a little silver to one and you see only yourself," the old man said. "That is your problem."

Copyright ©1999 A.D. Sullivan

All work is by A.D. Sullivan except where otherwise indicated.

Those who wish to comment can send comments to A.D. Sullivan